Explainer: What exactly is “Vote Chori”? What are the allegations of opposition upon the BJP?

Lately, you might have seen the phrase “Vote Chori” all over political discussions. Literally meaning “vote theft” in Hindi, it refers to the alleged large-scale tampering with India’s voter lists, and it has now snowballed into one of the most heated political controversies of 2025.

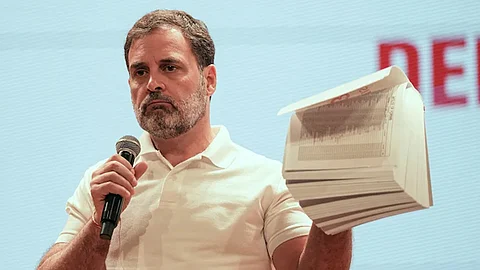

The buzz began earlier this month when Congress leader Rahul Gandhi accused the BJP of manipulating voter rolls on a massive scale. His focus? The Mahadevapura assembly segment in Bangalore Central. According to him, a six-month probe by the party uncovered over one lakh questionable entries in the rolls, out of a total of 6.5 lakh voters.

He alleged that the voter list is riddled with irregularities

11,965 people are shown as duplicate voters, registered at different polling booths.

In some cases, as many as 80 voters are registered from the same location, including the bizarre example of “House Number Zero” and even from commercial properties, adding up to 40,009 addresses that he claims are fake or invalid.

Invalid address, 10,452 voters are listed with incorrect residential adress it being just a single room.

There are 4,132 voter photographs that are either missing or don’t match. In several instances, the same person’s image appears multiple times under different names, sometimes shrunk to thumbnail size or cropped to extreme close-ups.

He also alleged that 33,692 voter IDs were created through the misuse of Form 6, a document intended for enrolling first-time young voters, but allegedly used for highly suspicious additions.

Gandhi didn’t stop at Karnataka. In Maharashtra, he says, more than one crore “new” voters suddenly appeared in the assembly poll lists, even though they hadn’t voted in the Lok Sabha elections earlier this year, with most of them, he claims, favouring the BJP.

The Congress argues that such “vote theft” can swing results in close contests. They’ve also accused the Election Commission of India (ECI) of looking the other way and even denying full access to digital voter rolls.

How did the Election Commission react?

The ECI was quick to push back, calling Gandhi’s accusations “misleading” and “baseless.” Their position is simple: if you have proof, you have to submit it formally under the rules, with names, addresses, and an affidavit.

For instance, Gandhi had highlighted a case where an elderly voter supposedly cast two votes. The ECI says they checked, and the woman confirmed she voted only once.

In short, the commission says it’s open to looking at errors but won’t act on speeches or press conferences alone, it wants detailed, official complaints.

So… is “Vote Chori” Just a Political Slogan, or a Real Threat?

Here’s the tricky bit. Fake or duplicate entries in voter lists are not a new problem, they’ve been flagged for years, especially in urban areas with high migration. The difference this time is the scale of the accusation and the political heat around it.

Large-scale national-level fraud hasn’t been proven publicly. But small-scale errors and even intentional padding of voter rolls? They’re real, and parties across the spectrum have complained about them at different times.

The Supreme Court is also keeping a watch, saying it will intervene if there’s “mass exclusion” or major mistakes in the ongoing voter roll revision drives.

Why this matters beyond politics

Whether the allegations are proven or not, one thing is certain: the noise around “Vote Chori” has shaken public trust. Opposition parties have taken to the streets, demanding more transparency. Online campaigns with names like “Stop Vote Theft” are cropping up.

For everyday voters, the concern is simple, if the rolls aren’t clean, can we really be sure that our vote counts fairly?

Altogether, Vote Chori is more than just a war of words between Congress and the BJP. It points to a genuine weak spot in our electoral system, keeping our voter lists accurate and up to date.

The ECI insists it is doing the work, cleaning rolls, inviting complaints, but won’t be swayed by press conference soundbites. The opposition says that’s not nearly enough.

One way or another, the outcome of this debate will shape not just future elections, but how much faith people have in the very idea of Indian democracy.